Last week I wrote about projections of future demand for Science, Technology, Engineering and Maths (STEM – or in Germany – MINT) occupations. I suggested that predictions of skills shortages were overstated.

The same applies to computer programmers. According to the European Commission, “many vacancies for ICT practitioners cannot be filled, despite the high level of unemployment in Europe. While demand for employees with ICT skills is growing by around 3% a year, the number of graduates from computing sciences fell by 10% between 2006 and 2010.

If this trend continues, there could be up to 900 000 unfilled ICT practitioners’ vacancies in the EU by 2015.”

This is not the first time the European Commission has predicted skills shortages for ICT practitioners. Prior to the Millennium bug, there were once more predictions of a massive shortage of programmers. And I suspect, with a little internet searching, it would be possible to find annual predictions of skills shortages and unfilled vacancies, especially from industry lobby bodies.

One reason for this, I suggested in my previous article, is that the ICT industry has an interest in keeping wages down by ensuring an over supply of qualified workers. In this respect, a report last week on the size and value of the apps industry in Europe is interesting. The report published by industry trade body ACT, claimed that there are currently 529,000 people in full-time employment directly linked to the app economy across Europe, including 330,000 app developers with another 265,000 jobs n created indirectly in sectors like healthcare, education and media, where apps are increasingly prominent.

At first glance then, this is a rosy area for young people with a good future. But digging deeper into the data suggests something different. According to the Guardian newspaper, “In the UK specifically, the report claims that 40% of organisations involved in developing apps are one-man operations, while 58% employ up to five people. It also points out that 35% of UK app developers are earning less than $1,000 a month from their work.”

1000 dollars a month is hardly a living wage, let alone a sufficient level of remuneration to justify the expense of a degree course. However this does not discourage the industry group who amongst other measures are lobbying the European Commission to strengthen the single market and develop “a flexible and supportive business environment for startups and entrepreneurs.” In other words, more deregulation.

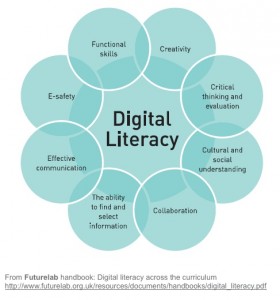

There are a number of problems in looking at skills shortages in this area. My suspicion would be that although the numbers graduating from computer science have fallen, graduates in computer and ICT related courses has risen. And demand for ICT practitioners covers a wide range of occupations. Rather than increasing the number of computer science graduates, more useful would be to ensure that ll graduates are skilled in designing and using new technologies. Of course developing such skills and competences should start at a much younger range. It is encouraging the ICT has been included in the primary school curriculum in England from next year.

The EU policy on future employment is based on the idea of job matching – of trying to match skills, qualifications and vacancies. Of course this does not work. What they should be doing is looking at prospective competences and skills – at giving young people the educations and skills to shape the future of workplace3s and employment. That could include the ability to use technology creatively in a socio-technical sense. But of course that would not suit the various industry lobby groups who are more concerned with protecting there profits than shaping the future of our society.