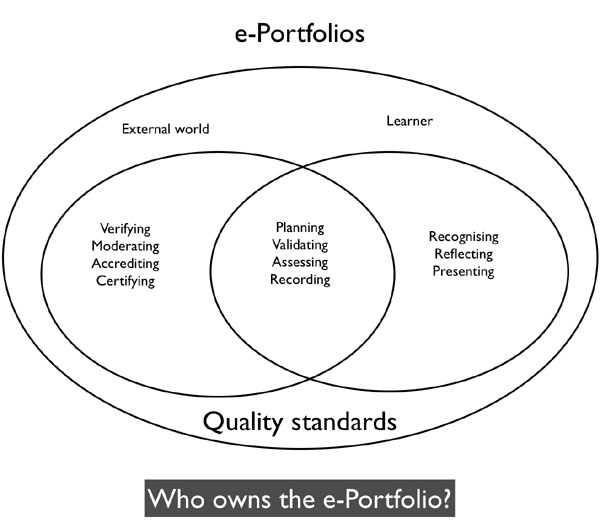

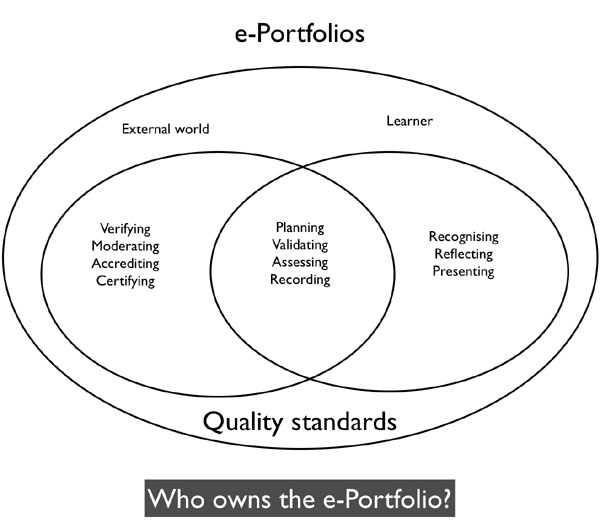

Over the years I have had a fair bit of interest, in this diagramme, produced in a paper for the the e-Portfolio conference in Cambridge in 2005.

I has some discussion about it with Gemma Tur at the PLE2012 Conference in Aveiro. And now Gemma, who is writing her doctoral dissertation in ePortfolios, has written to me to remind me of our discussion. Gemma says:

I thought I could add that eportfolios built with web 2.0 tools may have another process which is based on networking. Cambridge (2009, 2010) argues about the construction of two selves, the networked self and the symphonic self. The first is about documenting learning quickly, in everyday life, taking brief notes with short and quick reflection, sharing and networking. The second is about presenting learning, reorganizing learning, linking learning evidence, with longer and more profound reflection… no networking in this final stage, as it is an inner process

As I am working with learning eportfolios, with web 2.0 tools, networking is a learning process for my students. Therefore, they are building their networked self.

So, if I argue networking is an eportofolio process of web 2.0 eportfolios, who owns the process? Looking at your article and your illustration, I thought it could be a process owned by both the learner and the external world. If networking is a process of sharing, visiting, linking, connecting, commenting, does it mean that it involves both the learner and the audience? this is what I thought before you told me that it is the learner’s process for sure.

So do you think that definitely I should argue that it is only owned by the learner? Then although it could need someone else to comment and connect, in fact, the act of networking is the student’s responsibility? is this the reason why you think that?, do you think I should argue it is owned by the learner?

These are interesting discussion impacting on wider areas than ePortfolios. In particular I think the issue of control is important to the emerging MOOC discussion.

Returning to Gemma’s questions – although I have not read the paper – I don’t think I agree with Cambridge’s idea of he networked self and the symphonic self – at least in this context. I think that networking becomes more important when presenting learning, reorganizing learning, linking learning evidence, and longer and more profound reflection. these processes are inherently social and therefore take place in a social environment.

However it is interesting that social networking was hardly on the radar as a learning process in 2005. And when I referred to the ‘external world’ I was thinking about external organisations – qualification and governmental bodies, trade unions and employers rather than broad social networks. Probably the diagramme needs completely redrawing to reflect the advent and importance of Personal Learning Networks.

However, despite the fact that personal social networks exist in the external world (the ‘audience’), I think the owner of the process is the learner. AZnd I would return again to Ilona Buchems study of the psychological ownership of Personal learning Environments. Ilona says:

One of most interesting outcomes of the study was the relation between control and ownership. The results show that while perceived control of intangible aspects of a learning environment (such as being able to determine the subject matter or access rights) has a much larger impact on the feeling of ownership of a learning environment than perceived control of tangible aspects (such as being able to choose the technology).

Personal Learning Networks are possibly the most important of the intangible aspects of a learning environment. The development of PLEs (which I would argue come out of the ePortfolio debate) and the connectivist MOOCs are shifting control from the educational institutions to the elearners and possibly more important from institutions to wider communities of practice and learning. Whilst up to now, institutions have been able to keep some elements of control (and monopoly through verifying, moderating, accrediting and certifying learning, that is now being challenged by a range of factors including open online courses, new organisations such as the Social Science Centre in Lincoln in the UK and Open Badges.

Such a trend will almost inevitably continue as technology affords ever wider access to resources and learning. The issue of power and control is however unlikely to go away but will appear in different forms in the future.