In December I wrote about a workshop I had attended at the Alpine-Rendezvous event organised by the European Stellar Network. The workshop: on ‘Technology-enhanced learning in the context of technological, societal and cultural transformation’ was organised by Norbert Pachler, the convenor of the London Mobile Learning Group (LMLG), housed at the Centre for Excellence in Work-based Learning for Educational Professionals at the Institute of Education, London.

The LMLG comprises an international, interdisciplinary group of researchers from the fields of educational, media and cultural studies, social semiotics and educational technology. The aim of the workshop was to augment the work of the LMLG, in particular around its socio-cultural ecology, and to extend the interdisciplinary nature of its work through exposure to perspectives advanced by (TEL) researchers in cognate fields from across Europe and the US, in particular in relation to design-based approaches.

This blog is an edited verion of Norbert’s report on the workshop. The full report will be published as part of proceedings of the workshop will be published as a Special Issue of the International Journal of Mobile and Blended Learning in 2010 guest edited by Norbert Pachler.

For me, one of the most interesting points about the recent debate around Open education is the exploration of the links between theory and practice. I have been long frustrated by the paucity of theory in the area of Technology Enhanced Education. and it is apparent that if we are to develop a convincing body of theory which can properly inform and reflect practice, it is necessary to engage in a multi-disciplinary discourse with researchers and practitioners coming from different fields of study and action.

The workshop in Garmisch comprised of an attempt at developing such a discourse and whilst the findings may represent only our early efforts to understand each other, I valued the opportunity to take part in such a discussion.

Norbert says:

“The LMLG sees learning using mobile devices governed by a triangular relationship between socio-cultural structures, cultural practices and the agency of media users / learners, represented in the three domains. The interrelationship of these three components: agency, the user’s capacity to act on the world, cultural practices, the routines users engage in their everyday lives, and the socio-cultural and technological structures that govern their being in the world, we see as an ecology, which in turn manifests itself in the form of an emerging cultural transformation. Another significant trend, which requires pedagogical responses, is the prevalence of what we call ‘user-generated contexts’. We are currently witnessing a significant shift away from traditional forms of mass communication and editorial push towards user-generated content and individualised communication contexts. These structural changes to mass communication also affect the agency of the user and their relationship with traditional and new media. Indeed, the LMLG argues that users are now actively engaged in shaping their own forms of individualised generation of contexts for learning through individualised communication contexts. New relationships between context and production are emerging in that mobile devices not only enable the production of content but also of contexts. They position the user in new relationships with space, i.e. the outer world, and place, i.e. social space. Mobile devices enable and foster the broadening and breaking up of genres. Citizens become content producers who are part of an explosion of activity in the area of user-generated content. What are the implications for education?

The workshop inter alia sought to explore the following questions and issues:

- Learning as a process of meaning-making for the LMLG occurs through acts of communication, which take place within rapidly changing socio-cultural, mass communication and technological structures. Does the notion of learner-generated cultural resources represent a sustainable paradigm shift for formal education in which learning is viewed in categories of context and not content? What are the issues in terms of ‘text’ production in terms of modes of representation, (re)contextualisation and conceptions of literacy? Who decides/redefines what it means to have coherence in contemporary interaction?

- What synergies are there between the socio-cultural ecological approach to mobile learning, which the LMLG developed (see Pachler, Bachmair and Cook, 2010), with paradigms put forward by different (TEL) research communities in Europe and beyond?

- What relationship is there between user-generated content, user-generated contexts and learning? How can educational institutions cope with the more informal communicative approaches to digital interactions that new generations of learners possess?

- What pedagogical parameters are there in response to the significant transformation of society, culture and education currently taking place alongside technological innovation?

Position papers and questions for discussion were made available in advance of the workshop on Google Groups as well as Cloudworks. During the workshop contributors’ presentations were added and participants in Garmisch and beyond contributed to the discussion on Cloudworks as well as on Twitter.

Key messages from the workshop:

The mixture of theory and practice was felt to have worked well and to have been fruitful particularly in view of a potential chasm developing between the research community and the policy and practitioner communities in the field of mobile learning.

The workshop underlined the importance of definitional clarity around key terminology, particular in the context of interdisciplinary work in an international context.

Mobile learning, the main focus of the workshop, can be seen to deal with complex issues, which benefit from an interdisciplinary approach. Despite interdisciplinarity adding complexity and this complexity needing to be managed sensitively, there exists a need for greater richness in the conceptual foundations of mobile learning; there is arguably a need to challenge the hegemony of education, psychology and computer science as the foundational disciplines of the mobile learning research community.

Some topics, such as sustainability, have proved to be multi-layered and the concurrent discussion of different layers during the workshopprovided fruitful insights into possible different framings of each given topic and issue.

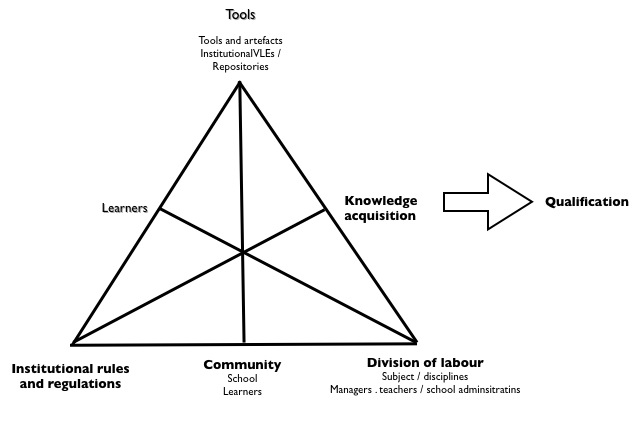

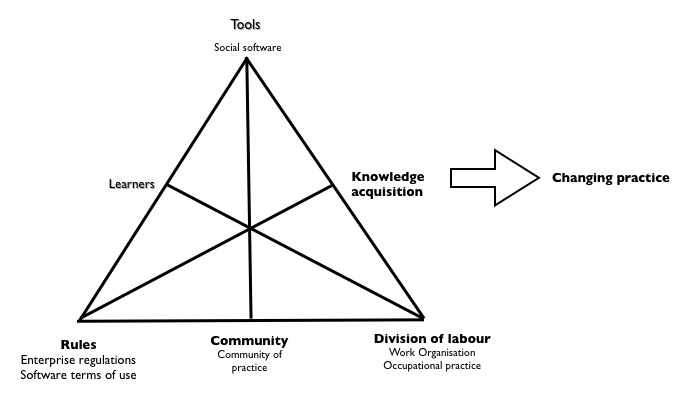

The workshop showed that the key theoretical framework used at the event for illuminating the use of mobile learning – the LMLG’s socio-cultural approach – has provided a useful lens and a shared vocabulary for analysis. At the same time it transpired that, in relation to some topics such as work-based learning, more work is required to align it and its theoretical underpinnings with established discourses in certain areas, such as WBL. Work-based mobile learning has to be embedded in the work-processes and current practices and not be designed as an extra layer. Structure in WBML is not only related to media platforms but also to organisational structures and focusing only on the first issue would be too narrow. Power-relationships are a central construct to be considered in WBML. And, the fact that businesses are orientated towards a productivity paradigm, rather than towards a learning paradigm, poses a particular challenge for WBML. A key question appears to be to what extent practices around mobile devices influence work-life balance.

The discussion around user-generated contexts demonstrated the complexity of the notion of context and how its different understandings are rooted in divers epistemological and ontological traditions.

The discussions around augmented reality brought to the fore a number of issues in particular around retention, perception and coherence as well as filtering and the need for criticality on the part of the user.

With respect to augmented contexts for development, the question arose whether Vygotskyan notions of perception / attention / temporality are a way forward and how these notions link in concrete terms to more academic / traditional views of ‘literacy’. And, what are the implications of for the emerging field of mobile augmented reality? Is it possible to replace the more capable peer in the zone of proximal development?

Synergies with design-based research were generally seen to offer considerable potential for the work of the LMLG and beyond. In particular, there emerged a strong sense of potential around the bringing together of a hermeneutic and critical historical approach to planning and analysis of teaching and learning, i.e. critical didactic, with the experimental, empirical evaluative approach offered by design research.

In terms of sustainability, the workshop concluded that much more still needs to be done in terms of understanding the complexity of the notion of sustainability. The discussion showed that there exists an important, and currently under-explored, ethical context to mobile learning, that is the context in which we connect with learners, composed in part of challenges such as sustainability, scalability (or transferability or replication), equity, inclusion, opportunity, embedding. It relates to a concern for the role of mobile learning for addressing forms of deprivation and disadvantage and informing the relevant policy environment.

Overall it can be noted that the discussions during the two days reiterated the need for a paradigm change in education to enable young people to deal with the implications of ongoing transformations.”

References:

Pachler, N., Bachmair, B. and Cook, J. (2010) Mobile learning: structures, agency, practices. New York: Springer