I have written periodic updates on the work we have been doing for the UKCES on open data, developing an open API to provide access to Labour Market Information. Although the APi is specifically targeted towards careers guidance organisations and towards end users looking for data to help in careers choices, in the longer term it may be of interest to others involved in labour market analysis and planning and for those working in economic, education and social planning.

The project has had to overcome a number of barriers, especially around the issues of disclosure, confidentiality and statistical reliability. The first public release of the API is now available. The following text is based on an email sent to interested individuals and organisations. Get in touch if you would like more information or would like to develop applications based on the API.

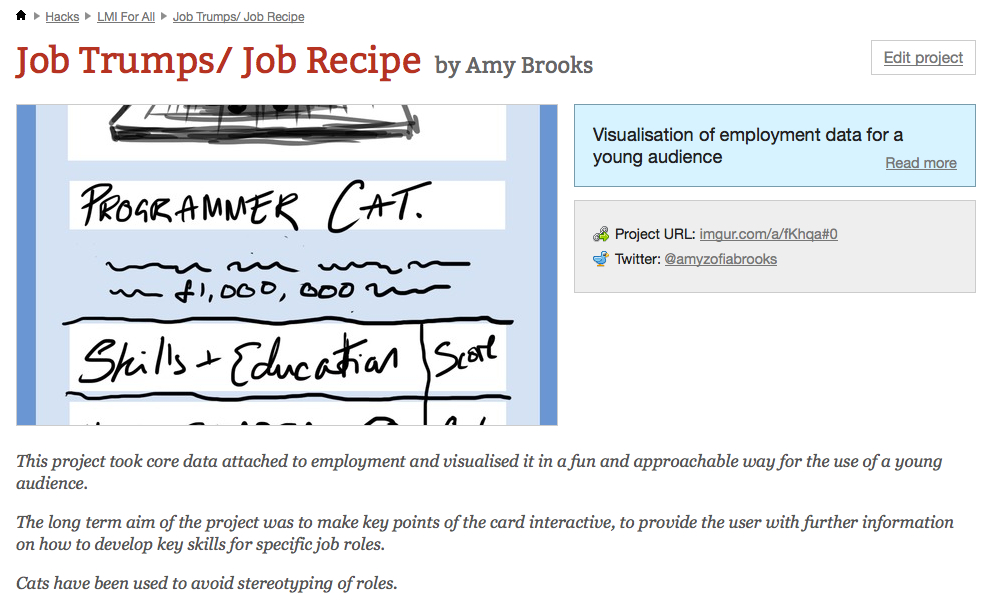

The screenshot above is of one of the ten applications developed at a hack day organised by one of our partners in the project, Rewired State. You can see all ten on their website.

The first pilot release of LMI for All is now available and to send you some details about this. Although this is a pilot version, it is fully functional and it would be great if you could test it as a pilot and let us know what is working well and what needs to be improved.

The main LMI for All site is at http://www.lmiforall.org.uk/. This contains information about LMI for All and how it can be used.

The APi web explorer for developers can be accessed at http://api.lmiforall.org.uk/. The APi is currently open for you to test and explore the potential for development. If you wish to deploy the APi in your web site or application please email us at graham10 [at] mac [dot] com and we will supply you with an APi key.

For technical details and details about the data go to our wiki at http://collab.lmiforall.org.uk/. This includes all the documentation including details about what data LMI for All includes and how this can be used. There is also a frequently asked questions section.

Ongoing feedback from your organisation is an important part of the ongoing development of this data tool because we want to ensure that future improvements to LMI for All are based on feedback from people who have used it. To enable us to integrate this feedback into the development process, if you use LMI for All we will want to contact you about every four to six months to ask how things are progressing with the data tool. Additionally, to help with the promotion and roll out of LMI for All towards the end of the development period (second half of 2014), we may ask you for your permission to showcase particular LMI applications that your organisation chooses to develop.

If you have any questions, or need any further help, please use the FAQ space initially. However, if you have any specific questions which cannot be answered here, please use the LMI for All email address lmiforall [at] ukces [dot] org [dot] uk.