The debate over skills shortages is looming again. For some years national governments and the European Commission have been warning over shortages of qualified workers in Science, Engineering, Technology and Maths (STEM) . Yet a number of studies refute these claims.

A blog post on SmartPlanet quotes Robert Charette who, writing in IEEE Spectrum, says that despite the hand wringing, “there are more STEM workers than suitable jobs.” He points to a study by the Economic Policy Institute that found that wages for U.S. IT and mathematics-related professionals have not grown appreciably over the past decade, and that they, too, have had difficulty finding jobs in the past five years. He lists a number of studies that refute the presence of a global STEM skills shortage. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, for one, estimates that there was a net loss of 370 000 science and engineering jobs in the U.S. in 2011.

I doubt that figures in Europe would be much different. One of the issues is how to define a ‘STEM” job. In the UK jobs are classified through a system called Standard Occupational Classification. This itself has its problems. Given the desire for comparability, SOC is only updated every ten years (the last was in 2010). In a time of fast changing occupations, it is inevitably out of date. Furthermore jobs are classified to four digits. This is simply not deep enough to deal with many real occupations. Even if a more detailed classification system was to be developed, present sample sizes on surveys – primarily the Labour Force Survey (LFS) would produce too few results for many occupations. And it is unlikely in the present political and financial environment that statistical agencies will be able to increase sample sizes.

But a bigger problem is linking subjects and courses to jobs. UK universities code courses according to the Joint Academic Coding System (JACS). It is pretty hard to equate JACS to SOC or even to map between them.

The bigger problem is how we relate knowledge and skills to employment. At one time a degree was seen as an academic preparation for employment. Now it is increasingly seen as a vocational course for employment in a particular field and we are attempting to map skills and competences to particular occupational profiles. That won’t really work. I doubt there is really a dire shortage of employees for STEM occupations as such. Predictions of such shortages come from industry representatives who may have a vested interest in ensuring over supply in order to keep wage rates down (more on this tomorrow). For some time now, national governments and the European Union, have had an obsession with STEM and particularly the computer industry as sources of economic competitiveness and growth and providers of employment (more to come about that, too).

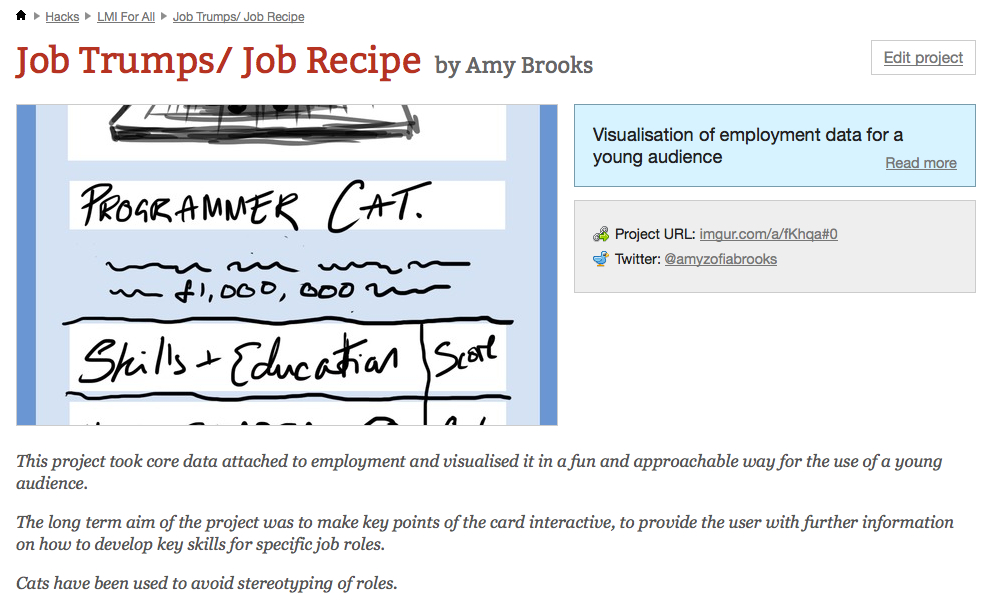

However, more important may be the number of occupations which require use of mathematics or programming as part of the job. One of the problems with the present way of surveying occupational employment is that there is an assumption we all do one job. I would be pretty pushed to define what my occupation is – researcher, developer, write, journalist, project manager, company director? According to the statistics agency I can only be one. And then how the one, whichever it is, be matched to a university course. Computer programmers increasingly need advanced project management skills. I suspect that one factor driving participation in MOOCs is that people require new skills and knowledge not acquired through their initial degrees for work purposes.

My conclusions – a) Don’t believe everything you read about skills shortages, and b) We need to ensure academic courses provide students with a wide range of skills and knowledge drawn from different disciplines, and c) We need to think in more depth about the link between education and work.