High or low skills? Graduate job or not?

For a number years now I have been working on projects developing the use of open data for careers counselling, advice and guidance. This work has been driven both by the increasing access to open data but also by the realisation of the importance of Labour Market Information (LMI) for those thinking about future education and / or jobs. And of course with high levels of job insecurity, such thinking becomes more urgent and in an unstable economy and labuor market, more tricky.

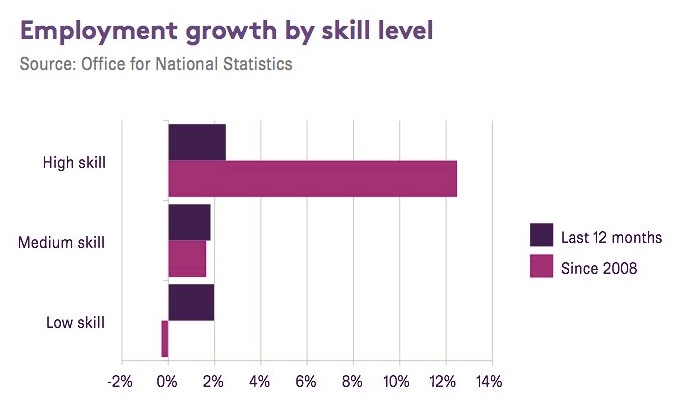

Yet even if we clean the data, add it to a database, provide and open API for access and develop tools for data visualisation, interpretation is still not easy. Here is one case, taken from this mornings Guardian newspaper.

Although the article is using the chart to show the rapid growth in knowledge intense occupations, I am not sure it does. Assuming that these are percentage change based on the original job totals, it probably show growth in low skilled jobs is far outstripping high skilled work, especially in the last 12 months. And that is taking into account that (once again probably) most job loss due to technology is focused din low skilled areas – e.g the quoted 70,00 jobs lost in supermarket check outs due to automation.

I am also interested to see from wonkhe that “The Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA) who have been running the Destination of Leavers Survey (DLHE) and its predecessors for 21 years, are now consulting widely on the future of assessing graduate outcomes.” For some time now there has been disquiet about the numbers of graduates working in ‘non graduate’ jobs. And that raises questions – just like the graph above focusing on high skills occupations – on just what a graduate job is. André Spicer, professor of organisational behaviour at the Cass Business School, City University London has cited “studies suggesting that the jobs which require degree-educated employees have peaked in 2000 and may be going down” and notes that many people apparently employed for their high-level specialist skills end up doing sales and marketing or fairly routine generalist work.

All this of course is highly subversive. Officially we are moving towards a high skilled economy needing more graduates and requiring higher level apprenticeships. My feeling in country slick Spain with high youth unemployment is what we need are apprenticeships in areas like construction and hospitality – both because they are sectors which can provide employment and also where higher skills are desperately needed to improve quality and productivity. Yet for governments there is an awful temptation to launch programmes in new ‘sexy’ areas like games technologies despite the scarcity of jobs in these fields.