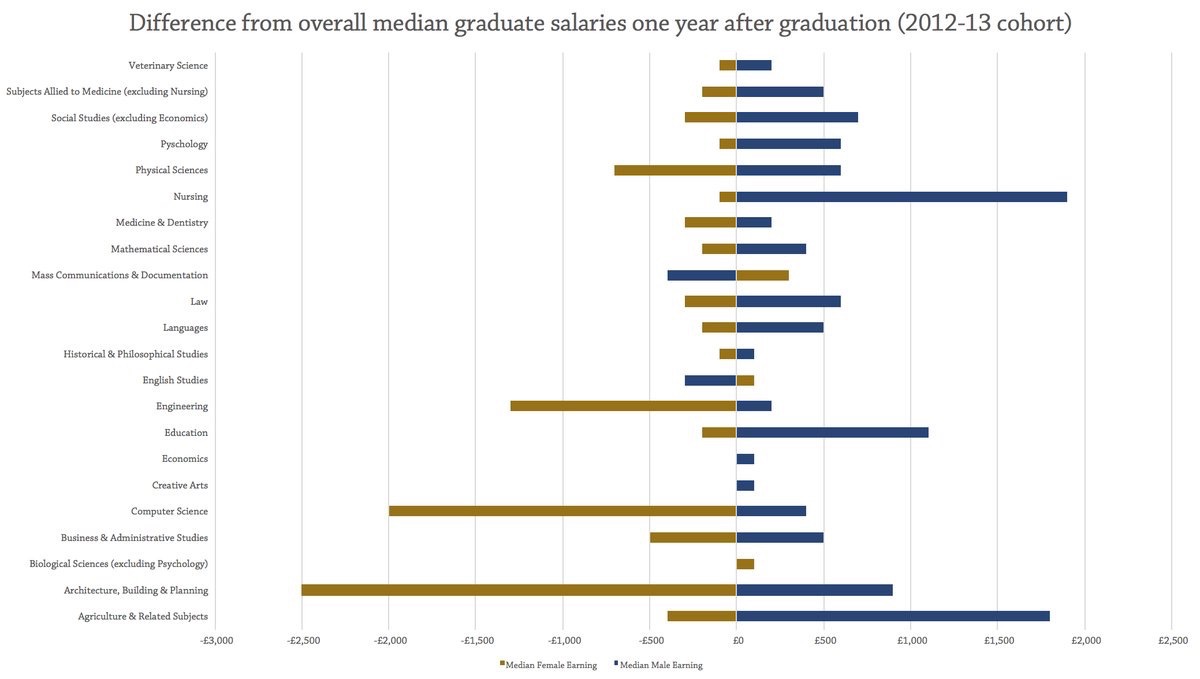

In our work on Labour Market Information Systems, we frequently talk about the differences between labour market information and labour market intelligence in terms of making sense and meanings from statistical data. The graph above is a case in point. It is one of the outcomes of a survey on Graduate Employment, undertaken by the UK Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA).

Like many such studies, the data is not complete. Yet, looking at the pay by gender reveals what WONKHE call “a shocking picture of the extent of the pay gap even straight out of university, and how different subject areas result in a diverse range of pay differences.”

Understanding why there is such a gap is harder. One reason could be that even with equal pay legislation, employers simply prefer to employ male staff for higher paid and more senior jobs. Also, the graph shows the subject in which the students graduated, not the occupational area in which they are employed. Thus the strikingly higher pay for mean who undertook nursing degrees may be due to them gaining highly paid jobs outside nursing. Another probable factor in explaining some of the pay gap is that the figures include both full and part time workers. Nationally far more women are employed part time, than men. However, that explanation itself raises new questions.

The data from HESA shows the value of data and at the same time the limitations of just statistical information. The job now is to find out why there is such a stark gender pay gap and what can be done about it. Such ‘intelligence’ will require qualitative research to go beyond the bald figures.

Interest in Vocational Education and Training (VET) seems to go in cycles. Its always around but some times it is much more to the forefront than others as a debate over policy and practice. Given the pervasively high levels of youth unemployment, at least in south Europe, and the growing fears over future jobs, it is perhaps not surprising that the debate around VET is once more in the ascendancy. And the debates over how VET is structured, the relation of VET to higher education, the development of new curricula, the uses of technology for learning, the fostering of informal learning, relations between companies and VET schools, the provision of high quality careers counselling and guidance, training the trainers – I could go on – are always welcome.

Interest in Vocational Education and Training (VET) seems to go in cycles. Its always around but some times it is much more to the forefront than others as a debate over policy and practice. Given the pervasively high levels of youth unemployment, at least in south Europe, and the growing fears over future jobs, it is perhaps not surprising that the debate around VET is once more in the ascendancy. And the debates over how VET is structured, the relation of VET to higher education, the development of new curricula, the uses of technology for learning, the fostering of informal learning, relations between companies and VET schools, the provision of high quality careers counselling and guidance, training the trainers – I could go on – are always welcome.